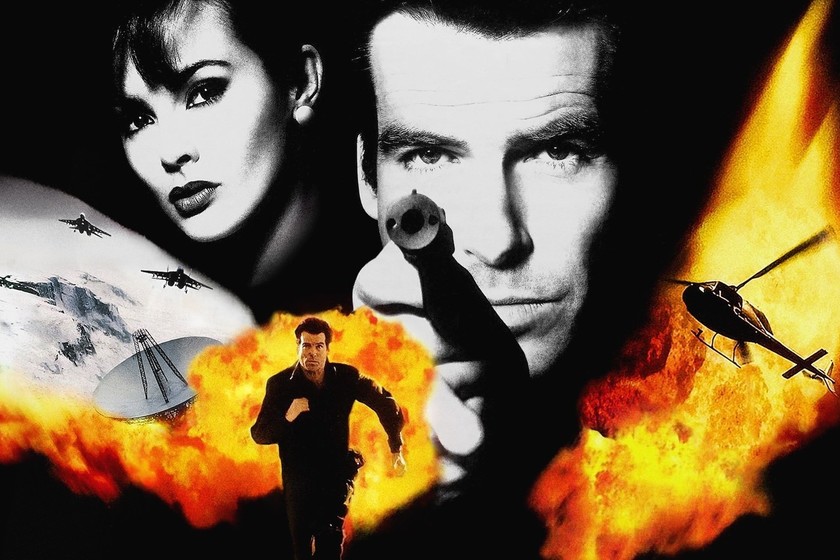

A decade ago, first-person shooters were for PC gamers and Rare made very pretty platformers. Then GoldenEye came along and changed everything. We gather together four of the original development team – Dave Doak, Steve Ellis, Karl Hilton and Graeme Norgate – to tell us how they turned a film licence for a mysterious new console into the definitive console FPS.

Pub bores the world over be silenced. We know who the best Bond is. It’s Roger Moore. Wait, come back. We have empirical evidence.

“Right near the end of development”, explains Dave Doak, “a guy came in from EON who owned the Bond licence and saw we had put in Connery, Dalton and Moore as well as Brosnan. We thought it would be great for marketing and even some screenshots went out with Connery in his white tuxedo.”

“Then an edict came down from on high and we had to get rid of the other Bonds, so on the day we had to take them out we played this epic deathmatch – first to a hundred kills – which went on for about three hours. Mark Edmonds played as Moore and won by one kill. It went down to the wire…”

GoldenEye’s enthralling multiplayer shootouts were thus denied an intriguing proposition. But then the game was never conceived as a four-player grudge match. In fact, it wasn’t even conceived as an FPS at all in the beginning.

Karl Hilton recalls the first mooting of the project: “I started at Rare in October 1994 and they had me modelling cars and weapons to see if I could do it for no particular game. Martin Hollis wandered in – he tended to float around – and said he was leading a team to do a Bond game.”

“I’d been highlighted as someone who might be interested and of course I was, but in the back of my mind I was thinking, oh God, a film licence. The previous ones had been 2D Robocop or Batman games and they were generally awful. It seemed a risky project.”

Initially, the intention was to do a 2D side-scrolling platformer for the SNES, a genre that Rare excelled in after the seminal Donkey Kong Country, but Hollis insisted the game should be in 3D and produced for Nintendo’s enigmatic Ultra 64, which was still in development. He also made explicit his design model: Sega’s lightgun arcade hit Virtua Cop.

Karl: “When I got involved, the first thing I did was model the gas plant. We put a spline through the level so you could follow a route like in Virtua Cop, but it didn’t go further than that. We decided to take it off the rails. Some of those early builds had bits missing because you’d never be able to see them and I remember going back and filling in the holes.”

GoldenEye was forging its own path, a departure from the Rare games that had gone before. When you consider that this was the first project for eight of the nine team members, that was perhaps to be expected. They may have been inexperienced, but they were unfettered by expectations of what a game could and couldn’t be.

They turned naivety into ambition and the enforced isolation of this happy band – “Rare organised teams into separate barns and you only had keys to your particular cell block”, quips Dave – meant that the newbies on the team had to find their own way.

“Because it was most people’s first game”, explains Graeme Norgate, “we did things we might not do again because it was too much work. We didn’t take the easy route. If something sounded like a good idea, it was like, ‘Yeah let’s do it!’ The world was our oyster! Only afterwards would you find it was a world of pain.”

At least it was a world of their own making. “It was untrammelled by arseholes”, explains Dave. “Nowadays, publishers get people who don’t know about games to run projects. We hadn’t worked on a game before but the difference was we were having to do the work.”

“Our wish-list of features would be things we knew would be good and we could do. There was some smart hiring and cherry-picking of people. We all had ambition and were hardworking. That’s how they managed to get that much content out of us.”

Martin also encouraged the team to draw on their love of the Bond films they’d grown up with. He recognised the inherent appeal of playing as the suave hero who had defined cool for so many aspiring young agents over the preceding decades. No longer would you simply be a floating gun as in Doom. Now you were England’s deadliest weapon.

Karl: “I remember the first time we got Bond’s hand in with the watch. We scanned it in and modelled it up and it had the cuff of the white tuxedo. I thought, hey, I’m James Bond! And then we put that thing in where the camera flies into the back of Bond’s head at the start of a level. It tied you in.”

A key part of that appeal was the infamous Licence to Kill. GoldenEye was a first-person shooter of course, but the decision to recognise body-specific hits introduced a new subtlety to the genre. Shoot a guard in the leg and he reacts differently to if you blasted him in the chest.

Each part of the body was given a weighting, expressed as a fraction. Hit a limb or the torso and your enemy would be pushed closer to a damage count of one and death. Or you could go straight for the head. A bullet in the brain equalled one. Instant death. One-shot kills.

Headshots were not only disturbingly satisfying though. They created a whole new way to play. Dave explains: “The way detection work was very simple but fundamentally changed the set-up. Whenever you fired a gun, it had a radius test and alerted the non-player characters within that radius.”

“If you fired the same gun again within a certain amount of time, it did a larger radius test and I think there was a third even larger radius after that. It meant if you found one guy and shot him in the head and then didn’t fire again, the timer would reset.”

“It wasn’t realistic but it meant the less you shot, the quieter you were, the less enemies came after you. If an NPC that hadn’t been drawn and was just standing in a room waiting was alerted by gunfire, it would duplicate itself and one went to investigate. You can see it happening sometimes – if you go to the right place and make a noise, you see more enemies spawning.”

Stay hidden, keep quiet, make every shot count… almost inadvertently, the team had invented stealth gaming. Of course you could still go in all guns blazing, but once players got to grips with the sniper rifle and realised that enemies had distinct blind spots to exploit – they could only ‘see’ you if they could walk to you in a straight line.

You could peer out from behind cover or line up a fatal headshot through windows – the sneaky approach was not only appealing, it was vital in successfully completing many of the game’s trickier missions. It was a surreptitious tactic that emerged naturally, rather than being pre-determined.

Karl: “When we had plenty of film material, we tried to stick to it for authenticity but we weren’t afraid of adding to it to help the game design. It was very organic. Dave would come in and say he needed an extra door and a room somewhere and we’d add it in. Back then, it was so much quicker. It’d be half a day’s work to add in a new corridor and a room.”

This sense of freedom to try new things, to experiment with level design, play it exhaustively and let the experience determine what direction development would go was crucial to how the team worked. They weren’t enslaved to a rigid design document, meaning everyone could contribute to game design. Nothing was set in stone. Not even the hardware.

Considering how the finished GoldenEye feels so suited to the N64, it’s easy to forget the machine didn’t exist for the first year and a half of its development. The team was using SGI Onyxs, hugely expensive Silicon Graphics machines, guessing at what the specs of Nintendo’s new console might be and using a butchered Saturn controller to playtest.

As it turned out, when they finally received the finished console they were pleasantly relieved. Despite costing a fraction of the SG workstations, fortunately Nintendo had come good on most of its promises. “The processor ended up being three quarters of what they had told us”, explains Steve. “We had to cut the textures down by half.”

Unfortunate, but not a disaster. And they coped with the reduction in admirable retro fashion. “A lot of GoldenEye is in black and white”, admits Karl, rather surprisingly. “RGB colour textures cost a lot more in terms of processing power. You could do double the resolution if you used greyscale, so a lot was done like that. If I needed a bit of colour, I’d add it in the vertex.”

As their semi-colourful Bond world was taking shape on the small screen, the film it was based on was nearing completion. The team had received the script very early in development and visited the set at Leavesden Studios, housed in an old Rolls Royce factory, half a dozen times.

“We had really good access”, says Karl. “We could walk anywhere and photograph what we needed. After the first few visits, I realised we needed textures. I started taking photos of walls!”

Visiting the filmset undoubtedly helped cement the game world in the minds of the team, but it also reminded Rare that the clock was ticking. While trying to release the game in tandem with the film had never been considered a viable proposition, the thought of it not appearing until the next Bond movie hit cinemas instilled an understandable sense of urgency.

Steve: “’It’s not your university project’ Tim Stamper told us one day! As heads of Rare, the Stampers probably had to make a lot of excuses. That’s what we have to do these days. Why isn’t it out yet? Why is it crap? We never had to answer those!”

Perhaps the Stamper Brothers’ greatest contribution to GoldenEye was fending off such enquiries and allowing the team time to develop a 3D game in what were still uncharted waters. Being able to play Mario 64 on the new console was a key influence.

Dave: “When Mario arrived it was clearly a step forward. Martin was obsessed with the collision detection, which was obviously doing it in 3D and GoldenEye was essentially using a 2D method. And our story was only about shooting stuff – we needed other things. We started putting in objectives, like meeting people in a level and back then that involved some complicated AI.”

“Finding Boris, guiding him through and making him decode something… that wasn’t easy! Other levels, you could hear the barrel being scraped – collect five arbitrary pieces and go here, but Mario had plenty of that shit, which is pretty boring. We punctuated it with stuff like go and blow this thing up! Like the canisters at the end of Arkhangelsk.”

“It’s in the film and we could have just said go here and press X – Karl had built that in the background but it wasn’t going to explode. But wouldn’t it be nice if it did? So the canisters became a ‘prop’. A bloody big prop. And the explosion had to be big enough to mask you switching one object with another.”

“But then if it’s a gas plant, shouldn’t we have gas? We can’t do f*cking gas, but we have got fog… maybe we could change the fog settings? Can we use that more than once? Maybe in the Egypt setting?”

For a game with more than its fair share of wanton destruction, the team became remarkably good at recycling. The radar on multiplayer mode is actually an oil drum texture, which explains the cloudiness on the right, and sometimes whole levels were created with the detritus they had to hand.

Karl: “As the engine got better, we were very good at reusing things. We decided we’d do the meeting room from Moonraker, which I just loved. We couldn’t do it round, that was just too expensive, but we did a square version and linked it with being under the shuttle. Dave said those chairs just have got to fold down like in the film so we did it with door code.”

“I remember one chair always folded wrong, but it would have taken so much coding to get it right, it was like, hey, leave it as a bug! The shuttle was made from reused satellite textures and to make it take off we used grenade explosions. That whole level is a big hack job, but it’s one of the nicest looking.”

GoldenEye was always good at giving you the big picture, from the dramatic bungee jump down Byelomorye dam at the opening to the final shoot out on the Antenna Cradle, but much of its enduring charm is in the detail. Bullet holes in glass, graceful forward rolls, hats being blown off heads and the knocking knees of terrified scientists.

“Those are Duncan Botwood’s knees”, laughs Karl. “He wasn’t a professional actor, he was one of the team! There was only one big motion-capture shoot and we realised someone was going to surrender at some point, so it was, ‘Put your hands up and shake your knees’. Then it would be, ‘Stand there and we’ll push you over’. I think we must have breached Health and Safety quite a lot…”

Graeme: “Duncan’s line was, ‘I had to die a million times for GoldenEye’. There were plenty of times when we’d get him to close his eyes and he didn’t know when he was going to be pushed. He went through a lot for the game. There was blood.”

It wasn’t the only occasion when the nearest warm body was put to good use. Alongside the faces of Pierce Brosnan, Robbie Coltrane et al, Bea Jones scanned in virtually all the staff at Rare. At the start of each level, five faces from the extensive collection are picked at random and plonked on the bodies of your adversaries. All the development team are in there and Karl remains rather proud of the manly scar added to his own mug. More cameos were to follow, explains Steve.

“There are a few monitors in the game – one has Dave in sunglasses and a Russian hat Karl had bought in Berlin, there’s one with Mark in a bowler hat on a skateboard and another has Karl doing a Python silly walk. We were just trying to make the monitors seem alive.”

A notable omission are the Stamper Brothers, who declined the opportunity to have their faces featured in the game, perhaps wary of giving employees the chance to shoot their bosses at close range. But the brothers’ faith in the project, protecting the team from outside interference and giving them the space to produce the best game they possibly could, means they can hold their heads high.

So many of the things that make GoldenEye special – the bonus Aztec and Egyptian levels, the AI that sees guards dashing for alarms and the wonderful multiplayer mode – were the result of not having to rush out a product to meet a demoralising deadline.

Steve: “The reason it turned out so well is that no one was standing over you saying you don’t need to do that, move on to the next bit. I was on the explosions for a month and I didn’t have someone telling me I’d had a week and that was enough. If there had been, the game might have been out on time…”

But it wouldn’t have been the game it turned out to be. The entire team flew out to E3 in 1997 to present a 99 per cent complete version of GoldenEye and while the game was well received, no one predicted the phenomenal success that followed.

A staggering 8 million copies were sold worldwide and it remains the biggest selling N64 game in the USA, outdoing Mario 64, Ocarina Of Time and Mario Kart. “Actually, I was concerned it wouldn’t be able to compete with Turok”, admits Karl. “That looked better and had a better frame rate… and dinosaurs!”

Laughter all round and an appropriate juncture for the team to pick up their pads and revisit the game that marked their entry into the industry. As Steve plays through the opening level, memories are triggered like sticky mines.

How Martin had done a 3D gun barrel that had to be dropped due to frame rate issues; how code had been written to let you drive the van, but it caused too many problems if you got the vehicle stuck in a dead end; how the unreachable island you can see far in the distance from atop the dam originally had a solitary guard patrolling it; how they’d had to label certain wall textures as ‘floor’ so guards could ‘see’ you, which meant they would occasionally leap out of bunkers inexplicably.

“At one point, we were going to have reloading done by the player unplugging and re-inserting the rumble pack on the controller”, remembers Steve. “Nintendo weren’t keen on that idea and I think it might have affected the pacing a bit…”

So to the main event – a ten-minute deathmatch – and as our four agents trade headshots and insults, they start to reel off the things GoldenEye pioneered. The sniper rifle, the gun disconnected from the camera, the civilian AI, the 3D explosions, the environment mapping (look closely at a shiny surface and you’ll notice a low resolution reflection of your surroundings), body-specific hit reactions and the tasty option of dual-wielding weapons. “Didn’t Halo 2 invent that seven years later?” chuckles Karl.

The list goes on, yet more fundamentally, they proved that a story driven FPS, a genre previously confined to PCs, could triumph on a console. Countless others have followed, but GoldenEye remains a benchmark.

And the winner? Appropriately enough, Steve, the creator of the multiplayer mode, nicks it by a single kill. Then the defeated trio realise he’s been playing as Oddjob, whose diminutive stature bestows a distinct advantage and the room echoes with cries of cheat and demands for a rematch.

GoldenEye: still inflaming passions ten years on.